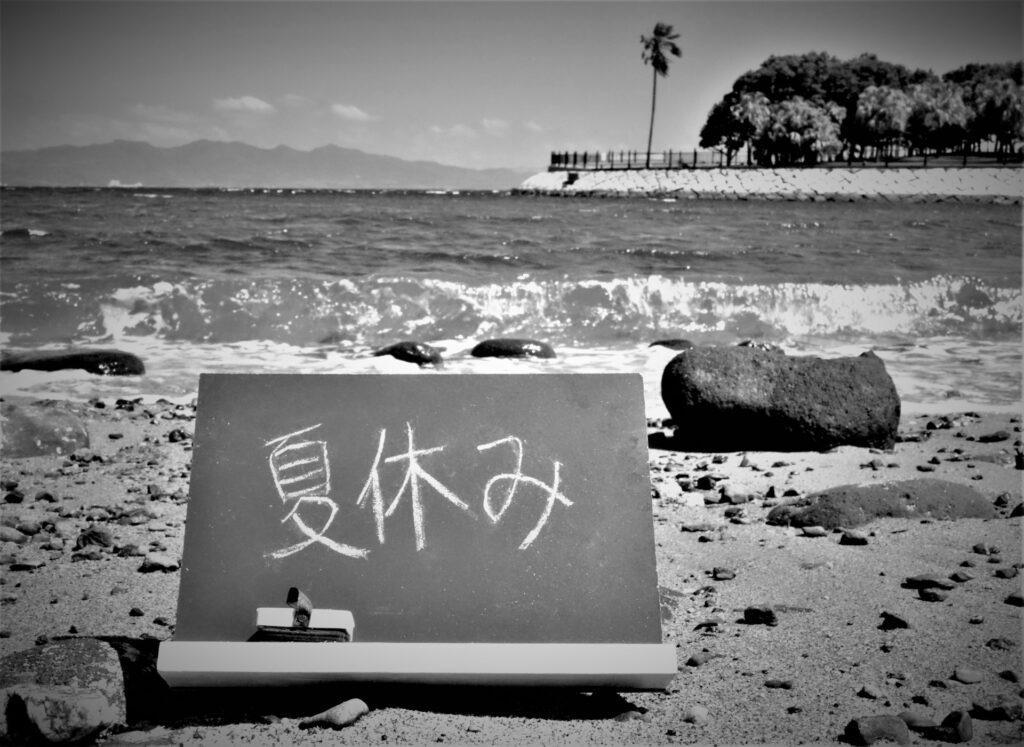

When summer arrives in Japan, it’s time for Japanese summer vacation — a short but treasured season filled with travel, festivals, and unique ways of coping with the heat. While today’s holidays might involve overseas trips, theme parks, and shopping malls, the history of summer in Japan stretches back centuries, evolving with the nation’s culture, technology, and lifestyle.

How Long Is Japanese Summer Vacation?

Unlike the long summer holidays common in Europe, Japanese summer vacation is relatively short. Elementary and junior high school students usually have about 40 days off, from late July to late August, while high school students often have slightly shorter breaks. Working adults do not typically receive a full summer holiday; instead, most take a few days off during Obon in mid-August, often combining paid leave to create a brief period away from work.

In Southern Europe, the rhythm is different. In Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Spain, school holidays often stretch for two to three months, allowing families to take extended trips or spend weeks in coastal villages. Many businesses slow down significantly in August, and adults may take two to four weeks off. This stands in contrast to Japan, where the limited time frame makes summer more condensed and activity-packed, with holidays often including a short beach visit, a trip to relatives, and perhaps a brief city break.

Edo-Era Summers: Cooling the Old-Fashioned Way

In the Edo period (1603–1868), surviving the summer heat meant relying on creativity and sensory pleasures rather than modern technology. One of the most famous traditions was uchimizu, the sprinkling of water in front of houses and along streets. The evaporation of this water helped cool the surrounding air, a fact understood through experience long before it was scientifically explained. The practice was celebrated in ukiyo-e prints and haiku, and it became a daily ritual for many.

People also sought comfort in sound, hanging wind chimes, or fūrin, from the eaves so their gentle ringing in the breeze created a sense of coolness. Early in the Edo period, glass was rare and wind chimes were luxury items reserved for the wealthy, but as glassmaking techniques spread, prices fell and street vendors began selling them widely. The visual image of goldfish swimming in small glass “kingyo-dama” bowls was another way to “feel” cooler. By the late Edo period, even common households could afford them, and families would often hang these delicate bowls under the eaves for decoration and enjoyment.

Leisure activities centered on natural water sources rather than the sea, which was not yet seen as a recreational space. People visited riversides, ponds, and waterfalls to cool down. The Ryōgoku river opening was a highlight of the summer, with fireworks lighting the night sky. Wealthy merchants and samurai floated in spacious yakatabune houseboats, while more modest, affordable boats eventually made this pleasure accessible to the common people. Another simple yet refreshing pastime was taki-ami — visiting waterfalls to enjoy their powerful cascades and, for the more adventurous, stepping into the spray for a natural shower.

-1-671x1024.jpg)

Meiji-Era Summers: The Birth of Sea Bathing

It was only in the Meiji period (1868–1912) that sea bathing became a popular leisure activity. Before this, people might enter the sea for work or health reasons, but rarely for fun. The transformation began with the expansion of the Tōkaidō Railway. In 1887, the line extended from Yokohama to Kōzu, and a year later, from Ōfuna to Yokosuka. These new routes made coastal areas far more accessible, and foreign residents in Japan — already accustomed to swimming for recreation — inspired the Japanese upper classes to try it themselves. Over time, sea bathing shifted from being a form of medical therapy to a recreational pastime, gradually spreading beyond the elite to the wider public.

Shōwa-Era Childhood Summers: Nostalgia and Community

In the Shōwa period (1926–1989), childhood summers were marked by a sense of community and simple pleasures. Days often began early with rajio taisō — radio calisthenics — in neighborhood parks at around 6:30 in the morning. Afterward, children might spend the day swimming in school pools, making shaved ice at home, and eating chilled sōmen noodles before taking an afternoon nap on tatami mats. Evenings were filled with quiet reading, the occasional half-hearted attempt at homework, and small fireworks in the garden.

For many, summer also meant boarding an overnight train to visit grandparents in the countryside, where they would help with chores in the morning and spend the afternoon playing in rivers or fields. In the 1980s, air conditioners began to appear in more homes, but many households still relied on electric fans, and school pools remained a vital escape from the heat.

From the 1960s to 2025: Changing Travel Trends

During the 1960s and 1970s, most families still had strong ties to rural hometowns, so summer vacations often revolved around visits to grandparents, afternoons spent fishing or catching insects, and trips to nearby rivers or mountains. In the 1980s, improved transport networks encouraged travel to mountain resorts such as Karuizawa or beach destinations like Izu and Okinawa, and theme parks such as Fuji-Q Highland became popular attractions.

The 1990s saw an increase in overseas travel to places like Hawaii, Guam, and Southeast Asia, while domestic tourism benefited from the Shinkansen linking more cities. In the 2000s, low-cost carriers and package tours made international travel even more accessible, and urban escapes such as Tokyo Disney Resort and Universal Studios Japan became must-visit destinations. By the 2010s, busier lifestyles meant shorter holidays, with many opting for quick domestic trips or urban leisure. The pandemic in the early 2020s shifted preferences temporarily toward domestic, nature-focused travel, but by 2025, both overseas and domestic tourism had rebounded, creating a balanced mix of destinations.

The Recent “Beach Detachment”

While beaches were once a central part of Japanese summer vacation, recent years have seen a decline in local beachgoing. Concerns about UV exposure and skin damage, the discomfort of crowded shores during the short holiday season, and the growing appeal of indoor, air-conditioned leisure have led many to choose shopping malls, theme parks, or overseas destinations instead. This marks a sharp contrast with countries like Greece or Cyprus, where beaches remain the heart of summer social life, with locals visiting daily to swim, dine, and relax by the sea.

Japanese Summer Vacation Today

From the gentle chime of Edo wind bells to Meiji’s seaside pioneers, Shōwa’s poolside afternoons, and today’s mix of tradition and modern tourism, Japanese summer vacation continues to adapt. Fireworks festivals, Bon Odori dances, and countryside retreats remain beloved, while sleek resorts, shopping districts, and international trips attract newer generations. However short the holiday, it remains a season of connection — with family, community, and the enduring spirit of summer in Japan.