Introduction — Why the Bear Problem Feels So Close to Home

In recent years, reports of bears wandering into Japanese towns and villages have surged. From farmlands and school routes in rural areas to suburban neighbourhoods, bear attacks in Japan that once seemed rare have become on the rise. While mountains have traditionally provided bears with ample food, changes in forest management, shifting climate conditions, and the availability of crops and garbage near human settlements are drawing bears ever closer.

Increasing Sightings and Attacks

In recent months, the bear issue has become alarmingly local for many Japanese communities. On July 12, 2025, a newspaper deliveryman was attacked by a brown bear in a residential area of Fukushima Town, Hokkaido. Reports indicate that he had encountered the same bear multiple times in the days leading up to the attack, and tragically, his body was discovered dragged into a nearby thicket. DNA evidence later confirmed it was the same animal responsible for a fatal attack on another resident four years earlier. https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20250712/p2a/00m/0na/002000c

Just a month later, on August 14, a 26-year-old man hiking Mount Rausu in Shiretoko—also in Hokkaido—was violently attacked and dragged into the forest by a brown bear. His body was discovered the next day following a search involving hunters and rescue teams, who also culled a mother bear and her two cubs in the vicinity. Authorities later closed the trail to ensure public safety. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20250814_14/index.html

These two tragic incidents underscore how bear encounters have moved from remote areas to more populated and frequented zones, making the problem feel far too close for comfort.

Following these fatal cases in Hokkaido, similar tragedies have also unfolded on Honshu. In early July 2025, an 81-year-old woman in Iwate Prefecture was killed by an Asiatic black bear, while other elderly residents in Aomori and Nara were also attacked in separate incidents. A few weeks earlier in Nagano, a man in his 40s gathering bamboo shoots was fatally mauled, and forestry workers in nearby Agematsu were injured in another bear encounter. These events show that the danger is not confined to Hokkaido’s brown bears but extends across Japan’s main island, where Asiatic black bears are increasingly coming into contact with people.

This is not an issue unique to Japan. Across Europe, people are facing similar struggles with wild animals entering human spaces. Wolves preying on livestock in Spain, brown bears appearing on the outskirts of Romanian towns, and wild boars causing accidents in Cyprus are all signs that the distance between humans and wildlife is shrinking. Ecosystems under pressure and human communities searching for balance have made the challenge of coexistence a global one.

Japan’s Bear Problem — Basics and Current Situation

Japan is home to two main species of bears. The brown bear, or Ursus arctos (called ‘higuma’ in Japanese), dominates Hokkaido and the smaller Asiatic black bear, or Ursus thibetanus japonicus (called ‘tsuki-no-waguma’ in Japanese), inhabits much of Honshu. Brown bears are larger and often more aggressive, while black bears are known for crop damage and occasional attacks on people in mountainous regions.

The reasons behind the increase in bear encounters are complex. Bear populations have recovered in recent decades as hunting has declined. Fluctuations in natural food supplies such as acorns and nuts drive bears toward farmlands and villages. Human expansion into mountain foothills has created more opportunities for encounters, and the food waste that humans produce attracts bears, while climate change has altered the timing and availability of seasonal foods. Another factor is the decline in hunters, as rural communities age and lose the human presence that once acted as an informal deterrent. As a result, bears now appear not only in agricultural fields but also near residential areas, school routes, and even hiking trails.

The types of damage are wide-ranging. Bears raid cornfields and orchards, destroy beehives in search of honey, and occasionally prey on livestock. Human injuries and fatalities, though still relatively small numbers, have tragically increased, as shown in recent high-profile cases in Hokkaido, where attacks resulted in deaths and sparked nationwide debate. Bears are also responsible for road accidents in mountainous regions, highlighting that the problem is not limited to rural farming communities.

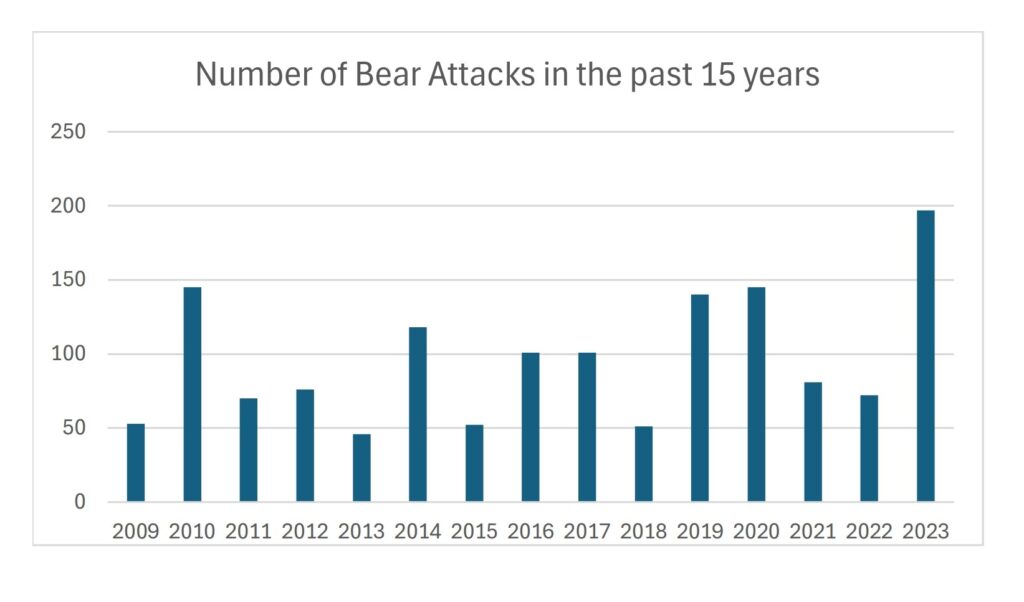

Recent government and media reports show an alarming rise in annual bear encounters. Hotspot maps highlight the forest edges and agricultural areas where incidents most often occur. Data comparing Japan with European countries reveals that this issue is not confined to one part of the world, but rather part of a wider pattern of human-wildlife conflict. Media coverage has amplified fears, while social networks circulate both reliable updates and misleading information. Public opinion is sharply divided between those demanding more aggressive culling and those who argue for coexistence and improved management.

Domestic Debate — Protection or Safety?

Japanese law allows the capture or killing of “problem bears,” but the criteria and speed of action differ by prefecture. Local governments follow a set of procedures that involve hunters’ associations, police, and emergency alerts, but compensation schemes for farmers affected by bear damage are often seen as inadequate. Experts stress the importance of habitat zoning, distinguishing core bear habitats from buffer zones, and they highlight the need for strict bans on feeding. The controversial practice of capturing bears and releasing them after conditioning—known as educational release—remains under debate.

One particular issue that illustrates the consequences of poor management is tourist feeding. In Shiretoko, for example, a young female bear nicknamed “Sausage” began associating people and vehicles with food after being fed by visitors. Over time, she lost her natural caution and ventured dangerously close to residential areas and even a school. Authorities were forced to put her down, a decision widely seen as a preventable tragedy. Such cases show that even small acts of feeding can set off a chain of dependency that ends in conflict and death for the bear.

Communities rely on various coexistence tools. Electric fences protect crops, garbage disposal is managed to avoid attracting animals, guard dogs are used in some areas, and bear spray has become more common among hikers. Schools organise patrols and reroute children when sightings are reported. Hunters’ associations, however, face increasing strain as their members age, while parents and teachers demand stronger protections. Tourism is also affected, as hiking and mountain attractions must now consider safety measures as a part of their appeal.

Public Opinion and Ethics — To Cull or To Coexist?

The ethical dilemma remains unresolved. On one side is the protection of human life and livelihood; on the other is the preservation of endangered wildlife and ecosystems. Social media accelerates the spread of information, but it also fuels rumours and fear. Clear, science-based risk communication is essential to help the public understand not only the risks but also the reasoning behind government decisions. Without this, trust erodes, and conflicts intensify.

Comparison — How European Countries Face Similar Wildlife Conflicts

Japan’s challenges echo those in Europe. Romania has the largest bear population in Europe, and many towns face bears entering residential areas, made worse by tourists feeding them. Debates there swing between conservationists and those advocating for controlled culling. In Italy’s Trentino region, reintroduced bears have attacked hikers, sparking lawsuits and fierce disputes over whether to capture or kill so-called “problem animals.” In Spain, wolves cause significant livestock losses. Farmers push for lethal control, but conservation laws keep wolves strictly protected, and compensation schemes often fail to satisfy those affected. In northern Greece, bears and wolves damage orchards and beehives, and NGOs work with municipalities on preventive measures such as fencing. Cyprus, while lacking large predators, faces similar challenges with wild boars and foxes damaging crops and causing traffic accidents. Even in smaller-scale cases, the balance between human activity and wildlife protection remains a difficult one.

Practical Approaches — Reducing Damage and Building Coexistence

Preventive measures are central to reducing conflicts. Physical tools such as electric fences, reinforced beehive boxes, bear spray, and stricter garbage management have proven effective. Human behaviour also matters. Parents and schools review walking routes for children, hiking groups adopt noise-making practices, and digital bear maps allow communities to avoid danger zones. Governance structures need strengthening, particularly in data sharing through apps and GIS, early-warning systems, and more efficient compensation schemes. Education and tourism also play a role, as anti-feeding campaigns and eco-tourism guidelines help people enjoy nature safely without making the problem worse.

Conclusion — Learning from Japan and Europe for Realistic Coexistence

Media and social networks must shift from fear-driven headlines to practical, actionable information that communities can use. Local knowledge is also invaluable; hunters, foresters, beekeepers, and hikers all possess on-the-ground insights that should inform policymaking. The key message is clear: there will never be zero risk when humans and wildlife share landscapes. The realistic goal is to reduce risks to acceptable levels and to build social consensus on how to live alongside these animals. The next step is to test and measure solutions at the local level, whether in schools, farmlands, or tourist destinations, and to continue refining strategies for coexistence.